Tuesday, July 24, 2007

Thoughts at the end of a long trip, 23rd July 2007 - ENGLISH

Naples, 23rd July 2007

South America is a special place. No doubt every stay in that continent - for short that was - leaves deep notalgic feelings. So deep that some people decide at some point to return back and live there for good.

Well, it is not my case - not yet, however! - but the sense of deepness I fell right now has stronger reasons than the simple nostalgy of a place, which is by itself already very strong. It is perhaps the lack of a more comprehensive condition, made by times and actions.

Many people asked me: "Silvio, weren't you missing your family, the friends, a fixed place where to stay? " Sure, but only during the pauses between two mountains! Everytime I was climbing a mountain nothing was missing because it was like the entire planet belonged to me. Perhaps sedentarity and nomadism are for me two alike conditions, one dependent from the other.

The Alps are the most beautiful montains in the world. It is a compact, dense, beautiful and aestethical range. The Andes, are the longest mountain range on Earth but do not have Alps' grace and beauty. But in South America I made the encounter with a dimension of alpinism totally different from what I had known so far. And not only because I made a major jump in the quality of my climbing level. It was trekking across the rugged Patagonia, climbing desperate routes in Peru, enjoying the desolate Atacama desert or travelling across the Bolivian plateau and climbing in the Cordillera Real that I truly encountered the mountain. My previous idea of physical confrontation against the mountain became suddenly obsolete.

My feet are still sore. The toes have been burned by the cold and even just walking is painful. But I cannot think to anything else than climbing. As soon again in good health I will start climbing using all of my spare time. I need to improve, and a lot, in rock-climbing; I need to improve technique, style and endurance. The objective is to have within the next sixteen months enough skill and try to climb the Cerro Fitz-Roy, probably one of the most beautiful mountains in the world. A vertical rock face, the most vivid expression of the pure essence of Patagonia. A land I left just a few months ago.

My return to the so-called active life will be in France. I leave tonight for Paris and from tomorrow I will have to hurry up to reinsert myself in the productive western society.

Returning to the "productive life" is right now an unavoidable choice, but I feel the real life is not there. Not for me, however. I don't know the psycology that explains my research of the limit. I just know that closer to that limit I feel alive. I do not have any joy in privations, in the pain, in the solitudine or when there's just an hair between me and the death. But it is only at proximity of the limit, when I move that frontier a little further away, that I can get the sense of the the human existence.

The toughts that express a value should not be understood but lived (H. Kessler, May 1986)

South America is a special place. No doubt every stay in that continent - for short that was - leaves deep notalgic feelings. So deep that some people decide at some point to return back and live there for good.

Well, it is not my case - not yet, however! - but the sense of deepness I fell right now has stronger reasons than the simple nostalgy of a place, which is by itself already very strong. It is perhaps the lack of a more comprehensive condition, made by times and actions.

Many people asked me: "Silvio, weren't you missing your family, the friends, a fixed place where to stay? " Sure, but only during the pauses between two mountains! Everytime I was climbing a mountain nothing was missing because it was like the entire planet belonged to me. Perhaps sedentarity and nomadism are for me two alike conditions, one dependent from the other.

The Alps are the most beautiful montains in the world. It is a compact, dense, beautiful and aestethical range. The Andes, are the longest mountain range on Earth but do not have Alps' grace and beauty. But in South America I made the encounter with a dimension of alpinism totally different from what I had known so far. And not only because I made a major jump in the quality of my climbing level. It was trekking across the rugged Patagonia, climbing desperate routes in Peru, enjoying the desolate Atacama desert or travelling across the Bolivian plateau and climbing in the Cordillera Real that I truly encountered the mountain. My previous idea of physical confrontation against the mountain became suddenly obsolete.

My feet are still sore. The toes have been burned by the cold and even just walking is painful. But I cannot think to anything else than climbing. As soon again in good health I will start climbing using all of my spare time. I need to improve, and a lot, in rock-climbing; I need to improve technique, style and endurance. The objective is to have within the next sixteen months enough skill and try to climb the Cerro Fitz-Roy, probably one of the most beautiful mountains in the world. A vertical rock face, the most vivid expression of the pure essence of Patagonia. A land I left just a few months ago.

My return to the so-called active life will be in France. I leave tonight for Paris and from tomorrow I will have to hurry up to reinsert myself in the productive western society.

Returning to the "productive life" is right now an unavoidable choice, but I feel the real life is not there. Not for me, however. I don't know the psycology that explains my research of the limit. I just know that closer to that limit I feel alive. I do not have any joy in privations, in the pain, in the solitudine or when there's just an hair between me and the death. But it is only at proximity of the limit, when I move that frontier a little further away, that I can get the sense of the the human existence.

The toughts that express a value should not be understood but lived (H. Kessler, May 1986)

Monday, July 23, 2007

Riflessione alla fine di un lungo viaggio, 23 luglio 2007 - ITALIANO

Napoli, 23 luglio 2007

L'America del Sud e' un posto un po' speciale. Non si puo' tornare - anche da un breve viaggio - da quel continente senza vivere da subito un minimo di nostalgia. Per qualcuno quella nostalgia diventa man mano sempre più’ insopportabile, al punto che a tanti capita ad un certo punto di farvi ritorno definitivamente.

Non e’ il mio caso - non ancora comunque! - ma il forte senso di vuoto che vivo adesso ha ragioni che sono più forti della nostalgia di un luogo, peraltro già essa stessa fortissima. E' piuttosto una condizione complessiva, marcata dai tempi e modi che ho dato alla mia vita per un anno, che manca. Molti mi chiedono: "Ma Silvio, non ti mancava la famiaglia, gli amici, avere un posto fisso? " Certo, ma solo nelle pause tra una montagna e l'altra! Ogni qualvolta mi sono trovato su una montagna niente mi è mancato perché era come se l'intero mondo mi appartenesse. O forse la sedentarietà' ed il nomadismo sono per me due condizioni l'una necessaria all'altra.

Le Alpi sono forse le montagne più belle al mondo. E’ una catena montuosa compatta,densa, bella, elegante e varia. Le Ande, pur essendo la catena montuosa più lunga della Terra non riescono lontanamente ad avvicinarsi alla loro grazia e bellezza. Però è nel continente sudamericano che ho fatto l’incontro con una dimensione dell’alpinismo totalmente differente da quella conosciuta fino ad allora. E non solo perché alpinisticamente durante l’ultimo anno ho fatto un netto salto di qualità. E’ stato nella ruggente Patagonia, nella durezza delle disperate ascensioni peruviane, del desolato deserto di Atacama o percorrendo l’altipiano boliviano in direzione della Cordillera Real che ho superato la dimensione della confronto con la montagna per entrare in quella dell’incontro.

I miei piedi sono ancora doloranti. I polpastrelli degli alluci sono bruciati dal freddo e mi è doloroso anche il solo camminare. Eppure io non riesco a pensare ad altro che al giorno del ritorno alla montagna. Appena lo stato di salute lo permetterà ricomincerò ad allenarmi usando tutto il tempo a disposizione che avrò. Devo migliorare, e molto, nell’arrampicata su roccia; devo migliorare tecnica, stile e resistenza. L’obiettivo è riuscire nel giro dei prossimi sedici mesi ad avere il livello sufficiente per provare realisticamente la scalata al Cerro Fitz-Roy, una delle più belle montagne al mondo. Una parete di roccia verticale che è forse l’espressione più intima e completa dell’essenza della Patagonia che ho lasciato qualche mese fa.

Il mio ritorno alla cosiddetta vita attiva si farà in Francia. Stasera parto per Parigi e da domani bisognerà darsi da fare per reinserirsi nella cinica e produttiva società borghese.

E pur essendo il ritorno alla "vita produttiva" una scelta attualmente inevitabile, non sento che la vera vita sia lì. Non lo è per me, ad ogni modo. Non conosco la psicologia che giustifica la mia ricerca del limite. Io so che solo quando mi avvicino a quel limite mi sento vivo. Non provo particolare gioia nelle privazioni, nel dolore, nella solitudine o nel sentire la morte che mi accarezza. Ma è solo a prossimità di quel limite, quando sposto quel limite un pò più in là, che riesco a cogliere l’intero senso dell'esistenza umana.

I pensieri che esprimono un valore non devono essere compresi bensi' vissuti (H. Kessler, maggio 1986)

L'America del Sud e' un posto un po' speciale. Non si puo' tornare - anche da un breve viaggio - da quel continente senza vivere da subito un minimo di nostalgia. Per qualcuno quella nostalgia diventa man mano sempre più’ insopportabile, al punto che a tanti capita ad un certo punto di farvi ritorno definitivamente.

Non e’ il mio caso - non ancora comunque! - ma il forte senso di vuoto che vivo adesso ha ragioni che sono più forti della nostalgia di un luogo, peraltro già essa stessa fortissima. E' piuttosto una condizione complessiva, marcata dai tempi e modi che ho dato alla mia vita per un anno, che manca. Molti mi chiedono: "Ma Silvio, non ti mancava la famiaglia, gli amici, avere un posto fisso? "

Le Alpi sono forse le montagne più belle al mondo. E’ una catena montuosa compatta,densa, bella, elegante e varia. Le Ande, pur essendo la catena montuosa più lunga della Terra non riescono lontanamente ad avvicinarsi alla loro grazia e bellezza. Però è nel continente sudamericano che ho fatto l’incontro con una dimensione dell’alpinismo totalmente differente da quella conosciuta fino ad allora. E non solo perché alpinisticamente durante l’ultimo anno ho fatto un netto salto di qualità. E’ stato nella ruggente Patagonia, nella durezza delle disperate ascensioni peruviane, del desolato deserto di Atacama o percorrendo l’altipiano boliviano in direzione della Cordillera Real che ho superato la dimensione della confronto con la montagna per entrare in quella dell’incontro.

I miei piedi sono ancora doloranti. I polpastrelli degli alluci sono bruciati dal freddo e mi è doloroso anche il solo camminare. Eppure io non riesco a pensare ad altro che al giorno del ritorno alla montagna. Appena lo stato di salute lo permetterà ricomincerò ad allenarmi usando tutto il tempo a disposizione che avrò. Devo migliorare, e molto, nell’arrampicata su roccia; devo migliorare tecnica, stile e resistenza. L’obiettivo è riuscire nel giro dei prossimi sedici mesi ad avere il livello sufficiente per provare realisticamente la scalata al Cerro Fitz-Roy, una delle più belle montagne al mondo. Una parete di roccia verticale che è forse l’espressione più intima e completa dell’essenza della Patagonia che ho lasciato qualche mese fa.

Il mio ritorno alla cosiddetta vita attiva si farà in Francia. Stasera parto per Parigi e da domani bisognerà darsi da fare per reinserirsi nella cinica e produttiva società borghese.

E pur essendo il ritorno alla "vita produttiva" una scelta attualmente inevitabile, non sento che la vera vita sia lì. Non lo è per me, ad ogni modo. Non conosco la psicologia che giustifica la mia ricerca del limite. Io so che solo quando mi avvicino a quel limite mi sento vivo. Non provo particolare gioia nelle privazioni, nel dolore, nella solitudine o nel sentire la morte che mi accarezza. Ma è solo a prossimità di quel limite, quando sposto quel limite un pò più in là, che riesco a cogliere l’intero senso dell'esistenza umana.

I pensieri che esprimono un valore non devono essere compresi bensi' vissuti (H. Kessler, maggio 1986)

Monday, July 16, 2007

The last act: "El Escudo", 8th-13th July 2007 - ENGLISH

Huaraz, 8th July 2007

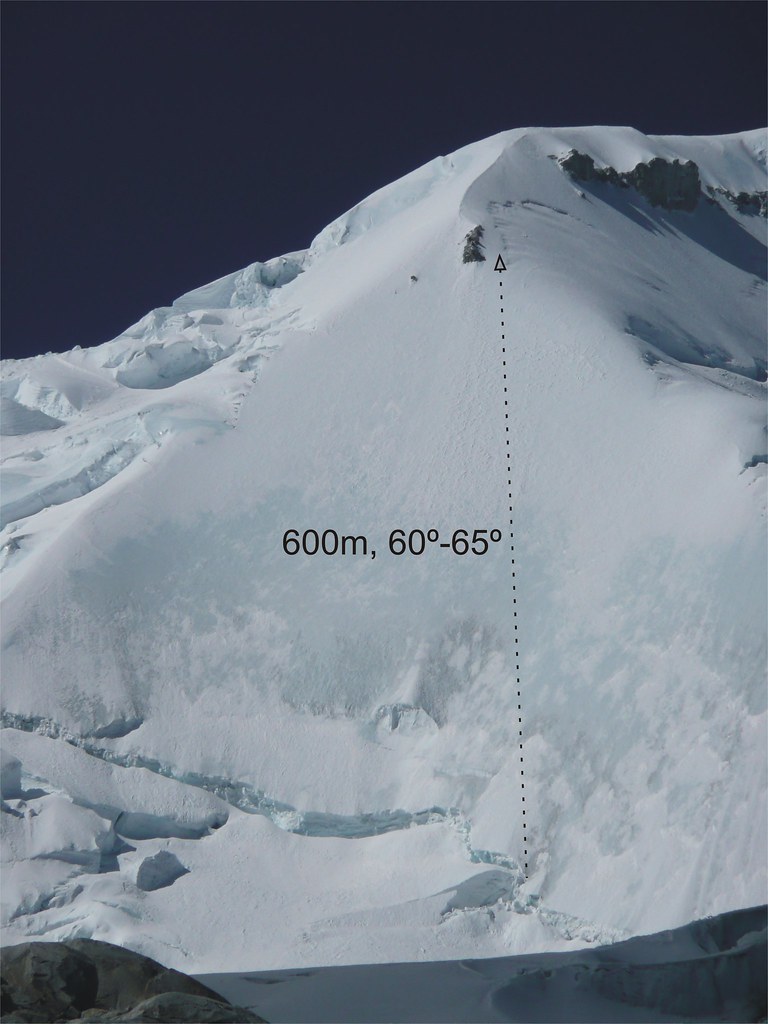

Ten days of climbing to go. Along the different options we have decided to climb the Huscaran, the highest mountain in Peru, by its West face called locally "El Escudo" ("The Shield"). This ice and snow face own such a name to its very peculiar triangular shape and can be climbed along different lines, the most frequented being the one on the leftest hand side. Our plan is to follow the normal route to the summit untill a altitude of 5900m, then attack the West face and climb about 400 metres at 55-60 degrees.

The "Shield" is a much more technical route than the normal but in itself it is not dangerous and if the weather is fine it will be a very enjoyable climb. Once the West face climbed we will descend the moutain along its normal route.

The ambition is to do everything in four days is pure alpine light style, setting a camp at the limit of the glacier (4800m) and one at the base of the "Shield" (5900m).

This is our last mountain, the last of my ten months' adventure.

Moraine camp (4800m), 9th July 2007

Today has been an hard day. We have left Huaraz in the morning in the direction of the Huscaran. Arrived in Musho, a tiny village at the base of the mountain, we started to hike up in the direction of the glacier's moraine. We arrived to the site selected for our first camp around 5pm. From here we can admire the "Shield" in all its beauty and power. The route normally cimbed is on the left and looks an easy climb, so easy that we wander what justifies the level of D+ (Difficult superior) assigned in our Peruvian climbing guides.

Camp glacier Huascaran (5700m), 10th July 2007

It has just stopped to snow, at least twelve inches in less than two hours. We camped at about 5700, just in the middle of the "Canaleta", a narrow gully just on Huscaran's normal route. The awful weather forced us to stop here. We do not know how fare or close we are from the base of the "Shield". If tomorrow the weather improves we will explore the area around us and climb the face the following day-

In half an hour I think I will get in the sleeping-bag, tomorrow it's another day.

Camp glacier Huascaran (5700m), 11th July 2007

Today bas been a nice day. Around 11am we left our camp to verify what is the most convenient point to start climbing the "Shield". On the left the access seems to be

blocked by a large dimensions crevasse, almost impassable; this makes the easiest route on the face not accessible. On the right it is possible to negotiate the large crevasse passing over a narrow but solid snow-bridge. Perhaps we haven't verified on the left all the possibilities to get to the easiest climbing route on the left. Speaking frankly we are seduced by the possibility to climb the face along a direct, aesthetical, without compromises route. However even if this last option is technically harder (the gradient is at least 60 degrees) it has the advantage to require a shorter approach, about one hour from our current camp. Personally I am convinced it is possible somehow to cross on the left the crevasse but Mike is of the opposite opnion. Doesn't matter, for me it's fine to climb the "Shield" on this direct line. This is the last mountain of my adventure in South America, I want to end well this trip. Tomorrow we plan to wake-up around 2am, leave the camp the latest 3am and around an hour later we expect to start climbing the face.

Huaraz, 13th July 2007

At the end also the "Shield" was climbed but it was not an easy victory. I will carry on myself the consequences per weeks.

Yesterday around 3am we left our camp at 5700m to get one hour later at about 5800m to the site selected to cross safely the large crevasse that traverse on all its lomgitude the West face. All fine in principle, but suddenly we have to face two issues. Mike's frontal lamp does not work correctly and starts flickering turning off at irregular times. We decide, however, to continue; arrived around 4am at the snow-bridge we decide to proceed as follows. I lead the first three pitchs of the climb (for a total of about 150 metres, 450 feet), after that it is will be 6am and there will be enough natural light to allow Mike to climb first. Unfortunately the bad luck is today persecuting us. As soon I start working with my ice-axes and my cromps on the wall MY frontal lamp starts to disfunction. At the minimal move it turns off. I found myself climbing an ice face with a gradient of 70 degrees in the full darkness, with the only company of the cold and the wind at almost 6000m. I manage, however to climb for sixty metres, the total lenght of the rope, placing correctly every ten metres the ice-screws to protect an eventual fall. Mike climbs the second pitch with its lamp that even if disfunctioning it is now better than mine. As soon we finish climbing the third pitch the light of the sun has become strong and we can stop the use of the artificial light. For the following seven hours we continue to climb the acros the six hundred metres of the wall. It is bitterly cold and the sun gets over the ridge only at 11am. The wall is cold, plastered with ice hard but fragile. We need to hammer with all our strenght ice-axes and crampons to penetrate them enough to sustain our weight. The wind blows continously making things certainly not easier.

It is with the biggest relief that just after 11am we got in proximity of the ridge. Just after noon the match is won, the face is completely climbed. About six hundred metres of ice at 70 degrees are below us. We are 6250m, the summit is five hundrerd metres higher. What it remains of the climb is now little more than am easy walk on an a snowy ridge but it would take at least three hours and the descend not less than five. In other words even if we do not take a single break (this si really unrealistic) and not make any mistake we would be back to our camp nto before 8pm. It is clear that allowing a couple of hours for a break and for some navigation's issues we can't be back before 10pm.

Conclusion: getting to the summit is out of question. And very honestly we could not bothered less. What we wanted was to climb the "Shield". The remaining part of the climb is now a walk of very little interest: returning back in the darkness for this is unjustified. Should I write again that our lamps are out of order? There is something else; after eight hours spent climbing on the face both Mitke and I are getting a potential I degree feet frost-bite.

Once the decision taken we quickly climb the ridge up to 6500m; from there it is possible to reconnect to the normal route. We descend it crossing crevasses and traversing sections where the snow gets to our chests. During the descend we realise that it was possible to access to the "Shield" on the left side if we had insisted a bit more exploring in that direction. Who really cares now? When the sun descends on the horizon we are only two hours from our camp. With the light of dusk and of my lamp that now works (bastard!) we get to our tent. It is 8pm, we spent the last seventeen hours climbing without a break, we are exhausted. My feet are are sore, the cold made my toes are black-blueish. Only a massive dose of pain-killers I manage to get asleep.

This morning we left the glacier early in the morning and after and intere day of hiking (from 5,7000 to 3,1000m) we got to the village of Musho and fron there to Huaraz. It has been a hard climb, my feet are sore as never before and I know several weeks - perhaps months - will be needed to recover. I don't mind, my adventure in South America ends with a big victory and even if a bit hurted I return back home safely and in one piece, only one year older.

Huaraz, 14th July 2007

Great: a new route, this is what we probably climbed. We didn't know but we climbed the hardest and most direct route of the entire face. We are verifying is this route had been not climbed before and so fare researchs are negative. May be my adventure in South America ends with the opening of a new route, the dream of any alpinist. This would be the greatest satisfaction even if at the price of a frostbite that will last, in the best of the cases, for a couple of months. Three days remain before my flight leaves Lima for Madrid and from there back to Italy. Seventy-two hours of well deserved rest!

Ten days of climbing to go. Along the different options we have decided to climb the Huscaran, the highest mountain in Peru, by its West face called locally "El Escudo" ("The Shield"). This ice and snow face own such a name to its very peculiar triangular shape and can be climbed along different lines, the most frequented being the one on the leftest hand side. Our plan is to follow the normal route to the summit untill a altitude of 5900m, then attack the West face and climb about 400 metres at 55-60 degrees.

The "Shield" is a much more technical route than the normal but in itself it is not dangerous and if the weather is fine it will be a very enjoyable climb. Once the West face climbed we will descend the moutain along its normal route.

The ambition is to do everything in four days is pure alpine light style, setting a camp at the limit of the glacier (4800m) and one at the base of the "Shield" (5900m).

This is our last mountain, the last of my ten months' adventure.

Moraine camp (4800m), 9th July 2007

Today has been an hard day. We have left Huaraz in the morning in the direction of the Huscaran. Arrived in Musho, a tiny village at the base of the mountain, we started to hike up in the direction of the glacier's moraine. We arrived to the site selected for our first camp around 5pm. From here we can admire the "Shield" in all its beauty and power. The route normally cimbed is on the left and looks an easy climb, so easy that we wander what justifies the level of D+ (Difficult superior) assigned in our Peruvian climbing guides.

Camp glacier Huascaran (5700m), 10th July 2007

It has just stopped to snow, at least twelve inches in less than two hours. We camped at about 5700, just in the middle of the "Canaleta", a narrow gully just on Huscaran's normal route. The awful weather forced us to stop here. We do not know how fare or close we are from the base of the "Shield". If tomorrow the weather improves we will explore the area around us and climb the face the following day-

In half an hour I think I will get in the sleeping-bag, tomorrow it's another day.

Camp glacier Huascaran (5700m), 11th July 2007

Today bas been a nice day. Around 11am we left our camp to verify what is the most convenient point to start climbing the "Shield". On the left the access seems to be

blocked by a large dimensions crevasse, almost impassable; this makes the easiest route on the face not accessible. On the right it is possible to negotiate the large crevasse passing over a narrow but solid snow-bridge. Perhaps we haven't verified on the left all the possibilities to get to the easiest climbing route on the left. Speaking frankly we are seduced by the possibility to climb the face along a direct, aesthetical, without compromises route. However even if this last option is technically harder (the gradient is at least 60 degrees) it has the advantage to require a shorter approach, about one hour from our current camp. Personally I am convinced it is possible somehow to cross on the left the crevasse but Mike is of the opposite opnion. Doesn't matter, for me it's fine to climb the "Shield" on this direct line. This is the last mountain of my adventure in South America, I want to end well this trip. Tomorrow we plan to wake-up around 2am, leave the camp the latest 3am and around an hour later we expect to start climbing the face.

Huaraz, 13th July 2007

At the end also the "Shield" was climbed but it was not an easy victory. I will carry on myself the consequences per weeks.

Yesterday around 3am we left our camp at 5700m to get one hour later at about 5800m to the site selected to cross safely the large crevasse that traverse on all its lomgitude the West face. All fine in principle, but suddenly we have to face two issues. Mike's frontal lamp does not work correctly and starts flickering turning off at irregular times. We decide, however, to continue; arrived around 4am at the snow-bridge we decide to proceed as follows. I lead the first three pitchs of the climb (for a total of about 150 metres, 450 feet), after that it is will be 6am and there will be enough natural light to allow Mike to climb first. Unfortunately the bad luck is today persecuting us. As soon I start working with my ice-axes and my cromps on the wall MY frontal lamp starts to disfunction. At the minimal move it turns off. I found myself climbing an ice face with a gradient of 70 degrees in the full darkness, with the only company of the cold and the wind at almost 6000m. I manage, however to climb for sixty metres, the total lenght of the rope, placing correctly every ten metres the ice-screws to protect an eventual fall. Mike climbs the second pitch with its lamp that even if disfunctioning it is now better than mine. As soon we finish climbing the third pitch the light of the sun has become strong and we can stop the use of the artificial light. For the following seven hours we continue to climb the acros the six hundred metres of the wall. It is bitterly cold and the sun gets over the ridge only at 11am. The wall is cold, plastered with ice hard but fragile. We need to hammer with all our strenght ice-axes and crampons to penetrate them enough to sustain our weight. The wind blows continously making things certainly not easier.

It is with the biggest relief that just after 11am we got in proximity of the ridge. Just after noon the match is won, the face is completely climbed. About six hundred metres of ice at 70 degrees are below us. We are 6250m, the summit is five hundrerd metres higher. What it remains of the climb is now little more than am easy walk on an a snowy ridge but it would take at least three hours and the descend not less than five. In other words even if we do not take a single break (this si really unrealistic) and not make any mistake we would be back to our camp nto before 8pm. It is clear that allowing a couple of hours for a break and for some navigation's issues we can't be back before 10pm.

Conclusion: getting to the summit is out of question. And very honestly we could not bothered less. What we wanted was to climb the "Shield". The remaining part of the climb is now a walk of very little interest: returning back in the darkness for this is unjustified. Should I write again that our lamps are out of order? There is something else; after eight hours spent climbing on the face both Mitke and I are getting a potential I degree feet frost-bite.

Once the decision taken we quickly climb the ridge up to 6500m; from there it is possible to reconnect to the normal route. We descend it crossing crevasses and traversing sections where the snow gets to our chests. During the descend we realise that it was possible to access to the "Shield" on the left side if we had insisted a bit more exploring in that direction. Who really cares now? When the sun descends on the horizon we are only two hours from our camp. With the light of dusk and of my lamp that now works (bastard!) we get to our tent. It is 8pm, we spent the last seventeen hours climbing without a break, we are exhausted. My feet are are sore, the cold made my toes are black-blueish. Only a massive dose of pain-killers I manage to get asleep.

This morning we left the glacier early in the morning and after and intere day of hiking (from 5,7000 to 3,1000m) we got to the village of Musho and fron there to Huaraz. It has been a hard climb, my feet are sore as never before and I know several weeks - perhaps months - will be needed to recover. I don't mind, my adventure in South America ends with a big victory and even if a bit hurted I return back home safely and in one piece, only one year older.

Huaraz, 14th July 2007

Great: a new route, this is what we probably climbed. We didn't know but we climbed the hardest and most direct route of the entire face. We are verifying is this route had been not climbed before and so fare researchs are negative. May be my adventure in South America ends with the opening of a new route, the dream of any alpinist. This would be the greatest satisfaction even if at the price of a frostbite that will last, in the best of the cases, for a couple of months. Three days remain before my flight leaves Lima for Madrid and from there back to Italy. Seventy-two hours of well deserved rest!

Saturday, July 14, 2007

L'ultimo atto: "El Escudo", 8-13 luglio 2007 - ITALIANO

Huaraz, 8 luglio 2007

Restano meno di dieci giorni alla partenza. Tra le differenti possibilita' abbiamo scelto di scalare il Huascaran, la montagna piu' alta del Peru', lungo la faccia ovest chiamata anche "El Escudo" ("Lo Scudo"). Il nome e' dovuto alla forma spiccatamente triangolare di questa parete di neve e ghiaccio che puo' essere scalata lungo diverse linee, la piu' frequentata e' quella che segue la cresta a sinistra. Il nostro piano e' di seguire la via normale alla vetta fino alla quota 5900m, quindi attaccare la parete ovest e scalare circa 400 metri con pendenza di 55-60 gradi.

Anche se si tratta di una ascensione assai piu' tecnica della via normale non si tratta di una via pericolosa e se il tempo ci assistera' credo che sara' assai piacevole. Una volta scalata l'intera parete scenderemo lungo la via normale.

L'obiettivo e' di farcela in quattro giorni in puro stile alpino leggero, allestendo un campo ai limiti del ghiacciaio (circa 4800m) ed uno alla base dello "Scudo" (5900m).

E' la nostra ultima montagna, l'ultima del mio viaggio di dieci mesi.

Restano meno di dieci giorni alla partenza. Tra le differenti possibilita' abbiamo scelto di scalare il Huascaran, la montagna piu' alta del Peru', lungo la faccia ovest chiamata anche "El Escudo" ("Lo Scudo"). Il nome e' dovuto alla forma spiccatamente triangolare di questa parete di neve e ghiaccio che puo' essere scalata lungo diverse linee, la piu' frequentata e' quella che segue la cresta a sinistra. Il nostro piano e' di seguire la via normale alla vetta fino alla quota 5900m, quindi attaccare la parete ovest e scalare circa 400 metri con pendenza di 55-60 gradi.

Anche se si tratta di una ascensione assai piu' tecnica della via normale non si tratta di una via pericolosa e se il tempo ci assistera' credo che sara' assai piacevole. Una volta scalata l'intera parete scenderemo lungo la via normale.

L'obiettivo e' di farcela in quattro giorni in puro stile alpino leggero, allestendo un campo ai limiti del ghiacciaio (circa 4800m) ed uno alla base dello "Scudo" (5900m).

E' la nostra ultima montagna, l'ultima del mio viaggio di dieci mesi.

Campo morena (4800m), 9 luglio 2007

Oggi e' stata una giornata abbastanza pesante. Abbiamo lasciato Huaraz in mattinata in direzione del Huascaran. Arrivati a Musho, il villaggio alla base della montagna, ci siamo incamminati verso la morena del ghiacciaio del Huascaran. Siamo arrivati al punto prescelto per il nostro primo accampamento verso le cinque del pomeriggio. Da qui lo "Scudo" si mostra in tutta la sua bellezza ed imponenza. La via normalmente percorsa e' a sinistra e sembra una scalata accessibile, al punto che ci chiediamo cosa giustifichi il livello di D+ (difficile superiore) che le e' assegnato nella letteratura di montagna del Peru'.

Oggi e' stata una giornata abbastanza pesante. Abbiamo lasciato Huaraz in mattinata in direzione del Huascaran. Arrivati a Musho, il villaggio alla base della montagna, ci siamo incamminati verso la morena del ghiacciaio del Huascaran. Siamo arrivati al punto prescelto per il nostro primo accampamento verso le cinque del pomeriggio. Da qui lo "Scudo" si mostra in tutta la sua bellezza ed imponenza. La via normalmente percorsa e' a sinistra e sembra una scalata accessibile, al punto che ci chiediamo cosa giustifichi il livello di D+ (difficile superiore) che le e' assegnato nella letteratura di montagna del Peru'.

Campo ghiacciaio Huascaran (5700m), 10 luglio 2007

Ha appena cessato di nevicare, ne sono caduti almeno trenta centimetri in meno di due ore. Siamo accampati a 5700m, nel mezzo della "Canaleta", uno stretto corridoio attraverso il quale si sviluppa la via normale al Huascaran. Il brutto tempo ci ha obbligato a sostare qui. Non sappiamo quanto siamo ancora lontani dalla base dello "Scudo". Se domani il tempo lo permettera' faremo una ricognizione dei luoghi e quindi scaleremo la parete dopodomani.

Fra una mezz'ora credo che piombero' nel sacco a pelo, domani e' un altro giorno.

Campo ghiacciaio Huascaran (5700m), 11 luglio 2007

Oggi e' stata una bella giornata. Verso le undici abbiamo lasciato la nostra tenda per verificare quale e' il luogo piu' conveniente per attaccare lo "Scudo". A sinistra la strada sembra essere bloccata da un crepaccio di grandi dimensioni, praticamente impassabile; questo rende la via di ascensione piu' facile non raggiungibile. A destra e' possibile negoziare questo crepaccio attraversando uno stretto ma solido ponte di neve. Forse non abbiamo verificato abbastanza la possibilita' di passare a sinistra e di raggiungere la classica via di scalata. In realta' siamo sedotti dalla possibilita' di scalare la parete lungo una via diretta, estetica, senza compromessi. Ad ogni modo questa opzione ben che tecnicamente piu' ardua (la pendenza e' almeno di 60 gradi) presenta il vantaggio di richiedere una marcia di avvicinamento assai breve, circa un'ora dal nostro campo attuale. Personalmente sono convinto che e' possibile attraversare il crepaccio a sinistra ma Mike e' di idea contraria. Poco importa, a me sta bene scalare lo "Scudo" per una via diretta. E' l'ultima montagna di questo viaggio, voglio un finale "con il botto". Domani la sveglia e'

alle due, lasceremo il campo alle tre ed alle quattro prevediamo di cominciare a scalare la parete.

Huaraz, 13 luglio 2007

Alla fine anche "Lo Scudo" e' stato scalato anche se non si e' trattato di una vittoria facile. Ne portero' addosso le conseguenze per settimane. Procediamo con ordine.

Ieri alle tre abbiamo lasciato il nostro campo a 5700m per renderci a 5800m nel luogo dove il giorno prima avevamo situato l'unico sicuro passaggio attraverso il vasto crepaccio che attraversa per tutta la sua longitudine la base della parete ovest. I problemi non si sono fatti attendere. La lampada frontale di Mike non funziona correttamente e si spegne ad intervalli irregolari. Decidiamo, comunque, di continuare; arrivati verso le quattro a 5800m decidiamo di procedere come segue. Io guidero' i primi tre tiri della scalata (in totale centocinquanta metri) ed a quel punto saranno le sei e ci sara' abbastanza luce solare perche' Mike mi dia il cambio. Purtroppo il diavolo ha deciso di metterci lo zampino. Appena comincio a lavorare con le picozze ed i ramponi sulla parte la MIA lampada frontale comincia a fare i capricci. Si spegne ad ogni minimo brusco movimento. Mi trovo a scalare una parete di 70 gradi nel pieno della notte - avvolto nel freddo e nel vento a quasi seimila metri - con una lampada che non funziona. Ad ogni modo riesco a scalare per sessanta metri, la lunghezza totale della corda, piazzando correttamente ogni dieci metri le dovuti viti da ghiaccio allo scopo di proteggere una eventuale caduta. Mike scala il secondo tiro con la sua lampada che seppur malconcia sembra funzionare meglio della mia. Appena termino di scalare il terzo tiro la luce solare e' diventata sufficiente per affrancarci dall'uso della luce artificiale. Per circa sette ore procediamo scalando i seicento metri che ci separano dalla sommita' della parete. Fa' freddo ed il Sole non compare che alle undici. La parete e' fredda, coperta di ghiaccio duro ma fragile. Dobbiamo insistere picchiando le picozze ed i ramponi affinche' penetrino in maniera sufficiente da sostenere il nostro peso. Il vento, che non cessa di soffiare un solo istante, non rende le cose certo piu' facili.

E' quindi con il massimo sollievo che poco dopo le undici ci approssimiamo alla sommita' della parete. Poco prima di mezzogiorno la parete e' vinta, e' completamente scalata. Seicento metri di ghiaccio e neve con pendenza fino a 70 gradi sono dietro di noi. Siamo a circa 6250m, la vetta del Huascaran e' cinquecento metri piu' in alto. La scalata a questo punto e' poco piu' ci una comminata lungo una cresta nevosa facile e poco inclinata ma richiede almeno tre ore e la discesa lungo la via normale ne richiedera' almeno cinque. Questo vuol dire che anche ammettendo di non prendere una sola pausa (e siamo ad oltre seimila metri) e di non fare alcun errore saremo di ritorno al nostro campo non prima delle otto di sera. Ammettendo un minimo di due ore per le inevitabili pause e per qualche "errore di percorso" ci risulta chiaro che non saremo di ritorno prima delle dieci della notte. Conclusione: di arrivare in vetta al Huascaran non se ne parla.

Ed a dirla tutta la cosa non ci interessa piu' di tanto. Quello che ci interessava era scalare "Lo Scudo". A questo punto cio' che resta fra noi e la cima e' una facile camminata, di poco interesse, che non giustifica il rischio di una discesa nell'oscurita'. Devo ricordare che le nostre lampade frontali non funzionano? Giusto per convincerci della giustezza della nostra decisione si aggiunge il fatto che dopo aver passato otto ore lavorando sulla parete ovest sia Mike che il sottoscritto stiamo soffrendo ai piedi di un probabile congelamento di I grado ai piedi.

Rapidamente procediamo lungo la cresta fino a 6500m, laddove e' possibile ricongiungerci con il percorso della via normale. Riscendiamo a questo punto il Huscaran negoziando crepacci ed attraversando sezioni dove affondiamo nella neve fino alla cintura.

Durante la discesa ci rendiamo conto che sarebbe stato possibile accedere allo "Scudo" a sinistra e percorrerlo per la via piu' facile se solo avessimo insistito nella ricerca di un passaggio da quel lato. Ma che importa ormai?

Quando il Sole cala dietro l'orizzonte siamo a due ore dal nostro campo. Con l'aiuto della luce del crepuscolo e della mia lampada che adesso sembra funzionare correttamente (stronza!) raggiungiamo la nostra tenda. Sono le otto, abbiamo passato le ultime diciassette ore scalando senza sosta, siamo fisicamente distrutti. Mi dolgono i piedi, i miei alluci sono nero-violacei a causa dell'intenso freddo subito e solo dopo una massiccia dove di antidolorifico riesco ad addormentarmi.

Stamattina abbiamo lasciato il ghiacciaio di buon'ora e dopo una intera giornata di discesa (da 5700 a 3100 metri) abbiamo raggiunto di nuovo il villaggio di Musho e da li' Huaraz.

E' stata una dura scalata, i piedi mi dolgono come mai in passato e so che per recuperare dai geloni che mi sono procurato occorreranno settimane, forse mesi. Ma non importa, la mia avventura in America del Sud si chiude con una vittoriosa scalata ed anche se un po' acciaccato torno in Europa sano e salvo, solo un anno piu' vecchio.

Stamattina abbiamo lasciato il ghiacciaio di buon'ora e dopo una intera giornata di discesa (da 5700 a 3100 metri) abbiamo raggiunto di nuovo il villaggio di Musho e da li' Huaraz.

E' stata una dura scalata, i piedi mi dolgono come mai in passato e so che per recuperare dai geloni che mi sono procurato occorreranno settimane, forse mesi. Ma non importa, la mia avventura in America del Sud si chiude con una vittoriosa scalata ed anche se un po' acciaccato torno in Europa sano e salvo, solo un anno piu' vecchio.

Huaraz, 14 luglio 2007

Grandioso: una nuova via, questo e' quello che abbiamo probabilmente scalato. Senza volerlo abbiamo scelto la via probabilmente piu' diretta e piu' dura. Stiamo verificando che la via non e' stata scalata in precedenza e sembra davvero che questo non sia il caso. Forse la mia avventura nell'altro emisfero si chiude con l'apertura di una nuova via, il sogno di ogni alpinista.

Sarebbe una grande soddisfazione anche se ottenuta a prezzo di un congelamento ai piedi che durera' al meglio un paio di mesi.

Adesso mi restano tre giorni di riposo prima che il mio aereo lasci Lima per Madrid e quindi da li' Napoli. Settantadue ore di meritato riposo!

Cordillera Huaywash, 25 giugno - 6 luglio 2007 - ITALIANO

Huaraz, 8 luglio 2007

Dopo una settimana passata scalando nella Cordillera Blanca continuiamo la nostra avventura nella Cordillera Huaywash, probabilmente la catena montuosa piu' selvaggia e meno scalata fra le principali del continente sudamericano, per circa dodici gioni.

Qui troverete il riassunto di undici intensi giorni passati in questa remota zona del Peru, il riassunto di quello che e' stata una vera avventura.

Scalare nella Cordillera Haywash e' stato davvero duro. I nostri obiettivi erano forse troppo ambiziosi, probabilmente al di la' delle nostre capacita'. Ed a dirla tutta le condizioni della neve e del ghiaccio non erano quelle sperate. Le montagne della Cordillera Haywash sono scalate molto raramente, e per raramente intendo che le principali sono scalate qualche volta in una diecina d'anni. Tutta l'organizzazione di questa spedizione e' pianificata con una mancanza strutturale di informazioni, ma questa e' una inevitabile parte del gioco.

Lasciamo Huaraz il 25 giugno sapendo che stiamo andando incontro ad una vera e propria esplorazione. L'intera catena montuosa non e' visitata da piu' di tre o quattro spedizioni in un anno e siamo perfettamente coscienti che laggiu' saremo soli. Naturalmente questo amplifica i rischi che corriamo, sappiamo che dovremo essere al cento per cento dipendenti da noi stessi.

Il nostro piano iniziale e' di scalare il Jirishanca - uno dei seimila metri piu' difficili delle Ande - lungo la "Via Cassin", una cresta nevosa scalata per la prima volta da una cordata di italiani che comprendeva i leggendari alpinisti Cassin e Ferrari.

Rapidamente ci rendiamo conto dei rischi oggettivi di scalare nella Cordillera Huaywash. Il terzo giorno, mentre stiamo risalendo la morena del ghiacciaio per stabilire il nostro secondo campo sentiamo un forte rumore venire da una vicina montagna Una enorma valanga di neve polverosa ha appena attraversato la parete ovest del Rondoy. Qualunque alpinista che si fosse trovato li' sarebbe stato trascinato mille metri piu' giu', anche se ancorato alla parete nel migliore dei modi possibile. Ci rendiamo conto che e' indispensabile scegliere una via di ascenso che sia potenzialmente il piu' possibile libera dal rischio di valanghe o di caduta di seracchi (facile a dirsi).

Appena stabiliamo il nostro secondo campo risulta evidente che attualmente non e' piu' possibile scalare il Jirishanca lungo la "Via Cassin". Negli ultimi sette anni il riscaldamento globale ha completamente distrutto la maggior parte di quella che era una via classica di ascensione. Dove prima v'era una elegante cresta verticale di neve e ghiaccio adesso c'e' solo ghiaccio vivo e roccia. Con l'obiettievo di evitare il rischio di valanghe e di caduta di seracchi decidiamo di scalare la montagna lungo la via anglo-americana, una via di neve e ghiaccio con una pendenza di circa 70 gradi che e' encora in buone condizioni. Dopo due giorni passati transitando sul ghiacciaio che circonda il Jirishanca nel tentattivo di trovare una via di accesso alla base della montagna ci diamo per vinti. E' chiaro che ormai la montagna e' totalmente circondata da una serie praticamente infinita di crepacci ed ed e' ormai accessibile solo ad una spedizione organizzata con mezzi che non sono stati contemplati nel nostro stile alpino leggero.

I nostri piani cambiano. Decidiamo di scalare il Yerupaja (6600m, la seconda montagna del Peru) un obiettivo possibilmente anche piu' difficile del Jirishanca. In meno di una giornata raggiungiamo un luogo sicuro del ghiacciaio ed a 5650 stabiliamo il nostro campo alto.

Il giorno dopo all'una del mattino ci muoviamo con l'intenzione di scalare il Yerupaja lungo una via diretta che percorre la faccia ovest. Dopo aver negoziato un difficile crepaccio alle tre cominciamo a sclare la faccia ovest, coperta da ghiaccio duro con inclinazione di crica 70 gradi. Il ghiaccio e' duro ma purtroppo non compatto, al colpo di picozza si frammenta senza garantire alcuna tenuta. Occorre tre volte piu' tempo per piazzare le nostre viti da ghiaccio. Siamo lenti e con il prossimo sorgere del Sole il rischio di una valanga e' alto. Negli ultimi giorni abbiamo osservato diverse valanghe a sinistra ed a destra della stretta via che stiamo scalando. In verita' la nostra via e' libera da rischi oggettivi ma il problema e' che alla nostra velocita' attuale abbiamo minime possibilita' di arrivare in vetta prima del tramonto. Su mia pressione poco prima di raggiungere 6000m decidiamo di interrompere la scalata e fare ritorno al campo. Ci sono piu' di quindici tiri di corda da scalare piu' la discesa. Davvero troppo.

Sotto le luci dell'alba possoi vedere il grandioso spettacolo dell'abisso che si apre sotto di noi. Credo che il novantanove per cento delle persone che conosco avrebbere un infarto stabdo qui solo per qualche secondo.

Ci riposiamo due giorni e decidiamo scalare un'altra montagna, il Rasac. La scalata e' classificta AD (abbastanza difficile) ma rapidamente ci rendiamo conto che e' molto piu' difficile di quanto preventivato. Dopo una lunga e travagliata scalata lungo una instabile e stretta cresta arriviamo in vetta, anche se tardi e dopo aver preso l'enorme rischio di scalare delle cornici di neve strabiombanti senza corda ne' protezioni su ghiaccio. La cresta del Rasac e' costituita da neve compatta ma sottile; cosi' sottile che ad un certo punto della scalata senza volerlo l'attraverso da parte a parte con la mia picozza scoprendo la vallata che e' ottocento metri piu' giu'. Immediatamente prendo una ragionevole distanza dall'estremita' della cresta cercando un compromesso tra le necessita' di procedere lungo la cresta e l'inevitabile rischio connesso.

Tutto sembra andare per il meglio ma lungo la discesa le cose cambiano. Ridiscendere il Rasac lungo la via di ascensione e' per me follia pura. Su mio suggerimento decidiamo di calarci in corda doppia lungo la rocciosa faccia est. Sono le quattro e mezzo del pomeriggio ed dobbiamo trovare una rapida via d'uscita. Alle sei siamo a soli 30-40 metri dalla base del ghiacciaio. Solo 30 o 40 metri e siamo fuori da questa maledetta parte di roccia marcia! Purtroppo non riusciamo a trovare uno sperone di roccia o una fessura dove realizzare un ancoraggio e l'inevitabile succede. E' notte e ci troviamo totalmente bloccati su una stretta terraza senza possibilita' di movimento. Siamo senza cibo, acqua, con abiti inadatti alla notte e siamo a 5700 metri senza altra possibilita' che aspettare che il Sole faccia il giro della Terra e torni a brillare su di noi.

Non possiamo dormire, perche' lo spazio a nostra disposizione e' appena sufficiente per sederci e non possiamo ancorare i nostri imbraghi a niente di solido. Se questo fosse possibile avremmo potuto abbandonare la parete; nell'errore di sottostimare la difficolta' della montagna non abbiamo portato con noi nessun chiodo da roccia. Addormentarsi equivale a cadere lungo la faccia rocciosa del Rasac.

Le dodici ore piu' lunghe della mia vita. In dodici ore ci sono 720 minuti, in 720 minuti oltre 43.000 secondi. Ogni secondo e' speso aspettando l'alba, pregando che questa fredda notte a 5700m finisca. Abbiamo freddo, fame e sete e dobbiamo alzarci ogni mezz'ora su questa stretta "terrazza", larga appena un metro, per riattivare la circolazione ed evitare che le nostre estremita' congelino (cio' che accade, anche se minimamente, al mio piede sinistro).

Ma non v'e' notte lunga abbastanza da non terminare ed alle sette il Sole e' di nuovi li' a riscaldarci. Mike scala uno sperone roccioso, trova un ancoraggio solido e piazza la corda. Scendiamo come ragni lungo la corda saldamente ancorata lungo la parete strabiombante, raggiungiamo finalmente il ghiacciaio e finalmente siamo di nuovo liberi di muoverci senza costrizioni. Il nostro campo e' a sole tre ore e da li' in circa tre giorni saremo di ritorno al villaggio piu' vicino.

Se fossimo delle persone normali avremmo dichiarato la nostra avventura in Peru terminata ma ci sono ancora nove giorni prima che i nostri aerei lascino Lima e vogliamo scalare almeno un'altra montagna. Domani lasceremo Huaraz per scalare il Huascaran, la piu' alta montagna del Peru' (6770m). E vogliamo scalarla lungo una via impegnativa, la parete Ovest chiamata anche "El Escudo" ("Lo Scudo). Cibo, materiale, informazioni e logistica e' stato organizzato durante gli ultimi due giorni. Speriamo di completare questa scalata in quattro giorni, in una settimana saprete se avremo avuto successo.

Dopo una settimana passata scalando nella Cordillera Blanca continuiamo la nostra avventura nella Cordillera Huaywash, probabilmente la catena montuosa piu' selvaggia e meno scalata fra le principali del continente sudamericano, per circa dodici gioni.

Qui troverete il riassunto di undici intensi giorni passati in questa remota zona del Peru, il riassunto di quello che e' stata una vera avventura.

Scalare nella Cordillera Haywash e' stato davvero duro. I nostri obiettivi erano forse troppo ambiziosi, probabilmente al di la' delle nostre capacita'. Ed a dirla tutta le condizioni della neve e del ghiaccio non erano quelle sperate. Le montagne della Cordillera Haywash sono scalate molto raramente, e per raramente intendo che le principali sono scalate qualche volta in una diecina d'anni. Tutta l'organizzazione di questa spedizione e' pianificata con una mancanza strutturale di informazioni, ma questa e' una inevitabile parte del gioco.

Lasciamo Huaraz il 25 giugno sapendo che stiamo andando incontro ad una vera e propria esplorazione. L'intera catena montuosa non e' visitata da piu' di tre o quattro spedizioni in un anno e siamo perfettamente coscienti che laggiu' saremo soli. Naturalmente questo amplifica i rischi che corriamo, sappiamo che dovremo essere al cento per cento dipendenti da noi stessi.

Il nostro piano iniziale e' di scalare il Jirishanca - uno dei seimila metri piu' difficili delle Ande - lungo la "Via Cassin", una cresta nevosa scalata per la prima volta da una cordata di italiani che comprendeva i leggendari alpinisti Cassin e Ferrari.

Rapidamente ci rendiamo conto dei rischi oggettivi di scalare nella Cordillera Huaywash. Il terzo giorno, mentre stiamo risalendo la morena del ghiacciaio per stabilire il nostro secondo campo sentiamo un forte rumore venire da una vicina montagna Una enorma valanga di neve polverosa ha appena attraversato la parete ovest del Rondoy. Qualunque alpinista che si fosse trovato li' sarebbe stato trascinato mille metri piu' giu', anche se ancorato alla parete nel migliore dei modi possibile. Ci rendiamo conto che e' indispensabile scegliere una via di ascenso che sia potenzialmente il piu' possibile libera dal rischio di valanghe o di caduta di seracchi (facile a dirsi).

Appena stabiliamo il nostro secondo campo risulta evidente che attualmente non e' piu' possibile scalare il Jirishanca lungo la "Via Cassin". Negli ultimi sette anni il riscaldamento globale ha completamente distrutto la maggior parte di quella che era una via classica di ascensione. Dove prima v'era una elegante cresta verticale di neve e ghiaccio adesso c'e' solo ghiaccio vivo e roccia. Con l'obiettievo di evitare il rischio di valanghe e di caduta di seracchi decidiamo di scalare la montagna lungo la via anglo-americana, una via di neve e ghiaccio con una pendenza di circa 70 gradi che e' encora in buone condizioni. Dopo due giorni passati transitando sul ghiacciaio che circonda il Jirishanca nel tentattivo di trovare una via di accesso alla base della montagna ci diamo per vinti. E' chiaro che ormai la montagna e' totalmente circondata da una serie praticamente infinita di crepacci ed ed e' ormai accessibile solo ad una spedizione organizzata con mezzi che non sono stati contemplati nel nostro stile alpino leggero.

I nostri piani cambiano. Decidiamo di scalare il Yerupaja (6600m, la seconda montagna del Peru) un obiettivo possibilmente anche piu' difficile del Jirishanca. In meno di una giornata raggiungiamo un luogo sicuro del ghiacciaio ed a 5650 stabiliamo il nostro campo alto.

Il giorno dopo all'una del mattino ci muoviamo con l'intenzione di scalare il Yerupaja lungo una via diretta che percorre la faccia ovest. Dopo aver negoziato un difficile crepaccio alle tre cominciamo a sclare la faccia ovest, coperta da ghiaccio duro con inclinazione di crica 70 gradi. Il ghiaccio e' duro ma purtroppo non compatto, al colpo di picozza si frammenta senza garantire alcuna tenuta. Occorre tre volte piu' tempo per piazzare le nostre viti da ghiaccio. Siamo lenti e con il prossimo sorgere del Sole il rischio di una valanga e' alto. Negli ultimi giorni abbiamo osservato diverse valanghe a sinistra ed a destra della stretta via che stiamo scalando. In verita' la nostra via e' libera da rischi oggettivi ma il problema e' che alla nostra velocita' attuale abbiamo minime possibilita' di arrivare in vetta prima del tramonto. Su mia pressione poco prima di raggiungere 6000m decidiamo di interrompere la scalata e fare ritorno al campo. Ci sono piu' di quindici tiri di corda da scalare piu' la discesa. Davvero troppo.

Sotto le luci dell'alba possoi vedere il grandioso spettacolo dell'abisso che si apre sotto di noi. Credo che il novantanove per cento delle persone che conosco avrebbere un infarto stabdo qui solo per qualche secondo.

Ci riposiamo due giorni e decidiamo scalare un'altra montagna, il Rasac. La scalata e' classificta AD (abbastanza difficile) ma rapidamente ci rendiamo conto che e' molto piu' difficile di quanto preventivato. Dopo una lunga e travagliata scalata lungo una instabile e stretta cresta arriviamo in vetta, anche se tardi e dopo aver preso l'enorme rischio di scalare delle cornici di neve strabiombanti senza corda ne' protezioni su ghiaccio. La cresta del Rasac e' costituita da neve compatta ma sottile; cosi' sottile che ad un certo punto della scalata senza volerlo l'attraverso da parte a parte con la mia picozza scoprendo la vallata che e' ottocento metri piu' giu'. Immediatamente prendo una ragionevole distanza dall'estremita' della cresta cercando un compromesso tra le necessita' di procedere lungo la cresta e l'inevitabile rischio connesso.

Tutto sembra andare per il meglio ma lungo la discesa le cose cambiano. Ridiscendere il Rasac lungo la via di ascensione e' per me follia pura. Su mio suggerimento decidiamo di calarci in corda doppia lungo la rocciosa faccia est. Sono le quattro e mezzo del pomeriggio ed dobbiamo trovare una rapida via d'uscita. Alle sei siamo a soli 30-40 metri dalla base del ghiacciaio. Solo 30 o 40 metri e siamo fuori da questa maledetta parte di roccia marcia! Purtroppo non riusciamo a trovare uno sperone di roccia o una fessura dove realizzare un ancoraggio e l'inevitabile succede. E' notte e ci troviamo totalmente bloccati su una stretta terraza senza possibilita' di movimento. Siamo senza cibo, acqua, con abiti inadatti alla notte e siamo a 5700 metri senza altra possibilita' che aspettare che il Sole faccia il giro della Terra e torni a brillare su di noi.

Non possiamo dormire, perche' lo spazio a nostra disposizione e' appena sufficiente per sederci e non possiamo ancorare i nostri imbraghi a niente di solido. Se questo fosse possibile avremmo potuto abbandonare la parete; nell'errore di sottostimare la difficolta' della montagna non abbiamo portato con noi nessun chiodo da roccia. Addormentarsi equivale a cadere lungo la faccia rocciosa del Rasac.

Le dodici ore piu' lunghe della mia vita. In dodici ore ci sono 720 minuti, in 720 minuti oltre 43.000 secondi. Ogni secondo e' speso aspettando l'alba, pregando che questa fredda notte a 5700m finisca. Abbiamo freddo, fame e sete e dobbiamo alzarci ogni mezz'ora su questa stretta "terrazza", larga appena un metro, per riattivare la circolazione ed evitare che le nostre estremita' congelino (cio' che accade, anche se minimamente, al mio piede sinistro).

Ma non v'e' notte lunga abbastanza da non terminare ed alle sette il Sole e' di nuovi li' a riscaldarci. Mike scala uno sperone roccioso, trova un ancoraggio solido e piazza la corda. Scendiamo come ragni lungo la corda saldamente ancorata lungo la parete strabiombante, raggiungiamo finalmente il ghiacciaio e finalmente siamo di nuovo liberi di muoverci senza costrizioni. Il nostro campo e' a sole tre ore e da li' in circa tre giorni saremo di ritorno al villaggio piu' vicino.

Se fossimo delle persone normali avremmo dichiarato la nostra avventura in Peru terminata ma ci sono ancora nove giorni prima che i nostri aerei lascino Lima e vogliamo scalare almeno un'altra montagna. Domani lasceremo Huaraz per scalare il Huascaran, la piu' alta montagna del Peru' (6770m). E vogliamo scalarla lungo una via impegnativa, la parete Ovest chiamata anche "El Escudo" ("Lo Scudo). Cibo, materiale, informazioni e logistica e' stato organizzato durante gli ultimi due giorni. Speriamo di completare questa scalata in quattro giorni, in una settimana saprete se avremo avuto successo.

Saturday, July 07, 2007

Cordillera Huaywash, 25th June - 6th July 2007 - ENGLISH

Huaraz, 8th July 2007

After a week spent in the Cordillera Blanca we decide to move to the Cordillera Huaywash, perhaps the wildest and less climbed of the main South-American ranges, for about twelve days.

Hereafter there is a brief description of the eleven days we spent in this remote range, the resume of what has been on itself a small epic.

Climbing in the Cordillera Haywash was really hard time. Our plans were perhaps too optimistical, may be over our abilities. Also the conditions of the snow and the ice were not as we hoped. The mountains of the Cordillera Haywash are climbed very rarely, and for rarely I mean a few times in a decade. We planned everything, from the gear to the food with a structural lack of informations but this was the unavoidable part of the game.

We leave Huaraz on June the 25th knowing that we are going to perform a kind of exploratory alpinism. The whole range sees not more than three or four expeditions in a year and we are absolutely aware that we are going to be alone there. This of course amplifies the risks and the commitment.

Our initial plan is to climb Jirishanca - one of the most difficult 6000m mountain of the entire Andes - by the "Cassin route", a snow ridge climbed the first time by a team of the Italians including the legendary Cassin and Ferrari.

We realise very soon the objective danger of climbing in the Cordillera Huaywash. The third day, while we are hiking up on the moraine of a glacier in order to estabilish our second camp we hear a strong noise from a nearby mountain. A massive powder avalanche has just happened; any climber being there would be killed doesn't matter how tightly anchored. It is going to be compulsory to choose a climbing route the less is possible prone to this kind of problems (easy to say).

As soon we estabilish our second camp we realise it is impossible these days to climb Jirishanca by the "Cassin route". In the last seven years the glacier retreat distroyed the most of that classic route. Now hard blue ice and rock stand on what before was an elegant steep snow and ice line. In order to avoid bjective dangers (mainly avalanches and seracs' fall) we decide to climb the mountain by the Anglo-American route, a snow and ice route of about 70 degree inclination that is still in good condition. After two days spent navigating across the crevasses of the glacier sourrounding Jirishanca in the vain attempt to get to the base of the mountain we give up. It is clear the moutain is now totally crevasses-locked and accessible only with major effort and big means wich are excluded by our light alpine style.

Our plans move then to climb Yerupaja, a 6600m mountain (the second tallest of Peru)and possibly an even difficult target than Jirishanca. In less than a day we get to a safe spot on snow at 5650m and there we set-up our high camp.

The day after at 1am we move with the intention to climb Yerupaja by a direct route laying on its West face. We negociate a difficult berschrund, cross it and around 3am we start to climb the icy face with an inclination of about 70 degrees. The ice is hard but flaky, we take three times more time than usually to place our ice-screws. We are slow and with the sun rising up the risk of avalanche gets high. In the last days we have observed several avalanches on the right and the left of the narrow ice coulouir we are climbing. Our route seems free of objective risks but the issue is that at our current speed we have small chances to get to summit before sunset. Just before getting to 6000m under my pressure we agree to turn back, there are more than fiftheen 15 rope-lenghts to climb and all the down-climb. Really too much.

Under the light of the dawn we can see the grand show of the abyss laying under us. Perhaps 99% of the people I know would get a stroke only being here for a few seconds.

The time to rest and two days later we start a new climb, the broad mountain of Rasac. The climb is rated in our guides as AD (fairly difficult) but very soon we realise it is much more difficult than this. After a long and laborious climb on a precarious ridge we get to summit, albeit late and taking big risks climbing overhanging cornices with no rope nor ice protection. The ridge is made-up of snow compact but very thin; so thin that during the climb I manage inadverntly to pass it from a side to the other with my ice-axe showing up the view of the valley standing eight hundreds metres below. Immediately I take a reasonable distance from the end of the ridge trying to compromise between the necessity to progress on the ridge and the risks related to it.

Everything gets fine but on the way back things worsen. On my suggestion we decide to rappel the mountain along its rock face down to the base of the glacier rather than downclimbing the exposed ridge we climbed on the way up. It is 4.30pm and we need a fast way-out from there. It is 6pm when we got at only 30-40m from the glacier. Only 30-40m to get out of this damned wall made of rotten rock! We can't find a safe anchor to rappel down and the unavoidable happens. It gets dark and we find ourselves totally stucked on a narrow terrace with no possibilty of movement. It is night and we got no food, no water, only light clothes and we are at about 5700m with no other possibility than waiting the sun to make the round of the earth and return back to shine on us.

We can't sleep, because the space at our disposal is just enough to sit and there's no solid place where we can anchor. If any of us got asleep he would fall along the rock face.

The longest 12 hours of my life. In 12 hours there are 720 minutes, in 720 minutes over 43,000 seconds. Every second is spent begging for dawn, praying this bitter night at 5700m to finish. We are cold, thirsty and hungry and need to stand up on this "terrace", wide only a few feet, every half hour to re-activate our circulation and avoid our extremities to freeze (what happened, even if ar minor degree, to my left foot).

But there's no night long enough not to end and at 7am the Sun is there again, feeding us with its energy. Mike climb a rock spur and find a safe anchor, I descend as a spider the rope now safely anchored, along the overhanging rock face. We get on the glacier and finally can move freely again; the camp is only three hours down and from there in about three days we will back to the closest village.

Being normal persons we would declare our adventure finished here but there are still nine days before our flights leave from Lima and we want to climb at least another mountain. Tomorrow we leave to climb Huascaran, the highest mountain of Peru (6770m). We want to climb it by a difficult route, "The Shield". Everything (food, gear, informations on the route, transportation) has been sorted out in the last two days. We hope to complete this climb in the time of four days, in a week or so you are all going to know if we will have been succesful.

After a week spent in the Cordillera Blanca we decide to move to the Cordillera Huaywash, perhaps the wildest and less climbed of the main South-American ranges, for about twelve days.

Hereafter there is a brief description of the eleven days we spent in this remote range, the resume of what has been on itself a small epic.

Climbing in the Cordillera Haywash was really hard time. Our plans were perhaps too optimistical, may be over our abilities. Also the conditions of the snow and the ice were not as we hoped. The mountains of the Cordillera Haywash are climbed very rarely, and for rarely I mean a few times in a decade. We planned everything, from the gear to the food with a structural lack of informations but this was the unavoidable part of the game.

We leave Huaraz on June the 25th knowing that we are going to perform a kind of exploratory alpinism. The whole range sees not more than three or four expeditions in a year and we are absolutely aware that we are going to be alone there. This of course amplifies the risks and the commitment.

Our initial plan is to climb Jirishanca - one of the most difficult 6000m mountain of the entire Andes - by the "Cassin route", a snow ridge climbed the first time by a team of the Italians including the legendary Cassin and Ferrari.

We realise very soon the objective danger of climbing in the Cordillera Huaywash. The third day, while we are hiking up on the moraine of a glacier in order to estabilish our second camp we hear a strong noise from a nearby mountain. A massive powder avalanche has just happened; any climber being there would be killed doesn't matter how tightly anchored. It is going to be compulsory to choose a climbing route the less is possible prone to this kind of problems (easy to say).

As soon we estabilish our second camp we realise it is impossible these days to climb Jirishanca by the "Cassin route". In the last seven years the glacier retreat distroyed the most of that classic route. Now hard blue ice and rock stand on what before was an elegant steep snow and ice line. In order to avoid bjective dangers (mainly avalanches and seracs' fall) we decide to climb the mountain by the Anglo-American route, a snow and ice route of about 70 degree inclination that is still in good condition. After two days spent navigating across the crevasses of the glacier sourrounding Jirishanca in the vain attempt to get to the base of the mountain we give up. It is clear the moutain is now totally crevasses-locked and accessible only with major effort and big means wich are excluded by our light alpine style.

Our plans move then to climb Yerupaja, a 6600m mountain (the second tallest of Peru)and possibly an even difficult target than Jirishanca. In less than a day we get to a safe spot on snow at 5650m and there we set-up our high camp.

The day after at 1am we move with the intention to climb Yerupaja by a direct route laying on its West face. We negociate a difficult berschrund, cross it and around 3am we start to climb the icy face with an inclination of about 70 degrees. The ice is hard but flaky, we take three times more time than usually to place our ice-screws. We are slow and with the sun rising up the risk of avalanche gets high. In the last days we have observed several avalanches on the right and the left of the narrow ice coulouir we are climbing. Our route seems free of objective risks but the issue is that at our current speed we have small chances to get to summit before sunset. Just before getting to 6000m under my pressure we agree to turn back, there are more than fiftheen 15 rope-lenghts to climb and all the down-climb. Really too much.

Under the light of the dawn we can see the grand show of the abyss laying under us. Perhaps 99% of the people I know would get a stroke only being here for a few seconds.

The time to rest and two days later we start a new climb, the broad mountain of Rasac. The climb is rated in our guides as AD (fairly difficult) but very soon we realise it is much more difficult than this. After a long and laborious climb on a precarious ridge we get to summit, albeit late and taking big risks climbing overhanging cornices with no rope nor ice protection. The ridge is made-up of snow compact but very thin; so thin that during the climb I manage inadverntly to pass it from a side to the other with my ice-axe showing up the view of the valley standing eight hundreds metres below. Immediately I take a reasonable distance from the end of the ridge trying to compromise between the necessity to progress on the ridge and the risks related to it.

Everything gets fine but on the way back things worsen. On my suggestion we decide to rappel the mountain along its rock face down to the base of the glacier rather than downclimbing the exposed ridge we climbed on the way up. It is 4.30pm and we need a fast way-out from there. It is 6pm when we got at only 30-40m from the glacier. Only 30-40m to get out of this damned wall made of rotten rock! We can't find a safe anchor to rappel down and the unavoidable happens. It gets dark and we find ourselves totally stucked on a narrow terrace with no possibilty of movement. It is night and we got no food, no water, only light clothes and we are at about 5700m with no other possibility than waiting the sun to make the round of the earth and return back to shine on us.

We can't sleep, because the space at our disposal is just enough to sit and there's no solid place where we can anchor. If any of us got asleep he would fall along the rock face.

The longest 12 hours of my life. In 12 hours there are 720 minutes, in 720 minutes over 43,000 seconds. Every second is spent begging for dawn, praying this bitter night at 5700m to finish. We are cold, thirsty and hungry and need to stand up on this "terrace", wide only a few feet, every half hour to re-activate our circulation and avoid our extremities to freeze (what happened, even if ar minor degree, to my left foot).

But there's no night long enough not to end and at 7am the Sun is there again, feeding us with its energy. Mike climb a rock spur and find a safe anchor, I descend as a spider the rope now safely anchored, along the overhanging rock face. We get on the glacier and finally can move freely again; the camp is only three hours down and from there in about three days we will back to the closest village.

Being normal persons we would declare our adventure finished here but there are still nine days before our flights leave from Lima and we want to climb at least another mountain. Tomorrow we leave to climb Huascaran, the highest mountain of Peru (6770m). We want to climb it by a difficult route, "The Shield". Everything (food, gear, informations on the route, transportation) has been sorted out in the last two days. We hope to complete this climb in the time of four days, in a week or so you are all going to know if we will have been succesful.